SLAC X-Ray Beam Helps Uncover Blueprint for Lassa Virus Vaccine

A decade-long search ends at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource, where researchers from The Scripps Research Institute emerge with a clear picture of how the deadly Lassa virus enters human cells.

Before Ebola virus ever struck West Africa, locals were continually on the lookout for another deadly pathogen: Lassa virus. With thousands dying from Lassa every year – and the potential for the virus to cause even larger outbreaks – researchers are committed to designing a vaccine to stop it.

Now a team of scientists from The Scripps Research Institute (TSRI) has solved the structure of the viral machinery that Lassa virus uses to enter human cells. X-ray beams from the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL) at the Department of Energy's SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory gave the team the final piece in a puzzle they sought to solve for over 10 years.

Their study, published today in Science, is the first to show a key piece of the viral structure, called the surface glycoprotein, for any member of the deadly arenavirus family, and the new structure provides a blueprint to design a Lassa virus vaccine.

“This was a tenacious effort – over a decade – to conquer a global threat,” said Erica Ollmann Saphire, a professor of Immunology and Microbial Science from TSRI and senior author of the new study.

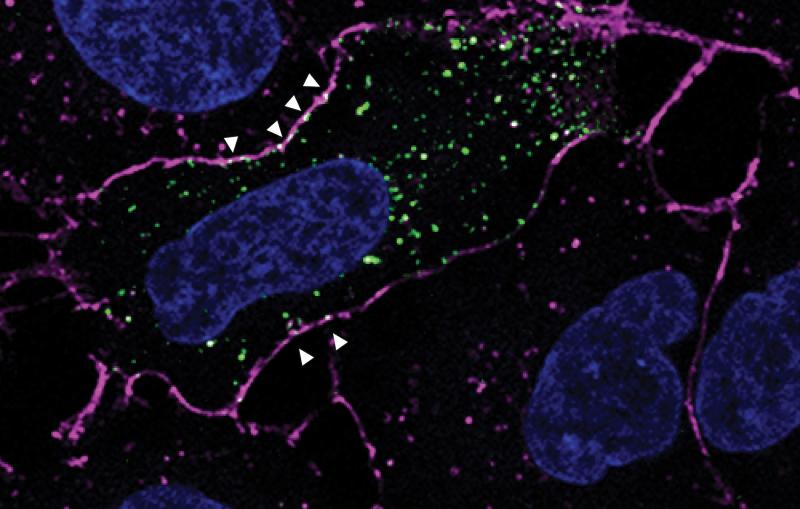

X-ray data for this study was collected at SLAC and the DOE's Argonne National Laboratory. For the SLAC experiments, the researchers used a station at SSRL, a DOE Office of Science User Facility that has a strong program in biological X-ray crystallography. In this method, scientists prompt biological molecules to align and form a crystal, which they then study with powerful X-rays. The way the X-rays scatter off the crystal reveals the structure of the molecules inside – in 3-D and with atomic detail.

"I am proud of SSRL’s strong partnership with TSRI and our involvement in this project that utilized the bright X-ray microbeams and high level of automation at Beam Line 12-2 to obtain the necessary data," said SSRL senior staff scientist Aina Cohen. "This structure provides key information towards engineering an effective vaccine against Lassa, enabling the infected to combat the immunosuppressive traits of this virus, which is estimated to kill tens of thousands of people each year."

It Started with a Thesis

The effort began with TSRI staff scientist Kathryn Hastie, the lead author of the study. In 2007, then a grad student in Ollmann Saphire's lab, she told her thesis committee she wanted to solve the structure of the assembled arenavirus glycoprotein, something never done before. She hoped to create a map of the target on the virus where antibodies need to attack – a key step in developing a vaccine.

Such maps can be obtained with X-ray crystallography, but the method depends on having a stable protein. Yet, all the Lassa virus glycoprotein wanted to do was fall apart.

The problem was that glycoproteins are made up of smaller subunits. Other viruses have bonds that hold the subunits together, “like a staple,” Hastie said. Arenaviruses don’t have that staple; instead, the subunits just floated away from each other whenever Hastie tried to work with them.

Another challenge was to recreate part of the viral lifecycle in the lab – a stage when Lassa’s glycoprotein gets clipped into two subunits. “We had to figure out how to get the subunits to be sufficiently clipped, which is necessary to make the biologically functional assembly, and also where to put an engineered staple to make sure they stayed together,” Hastie said.

Partnering with West Africa

As Hastie tackled those challenges from her lab bench in San Diego, staff at the Kenema Government Hospital in Sierra Leone labored on the front lines of the ongoing fight against Lassa.

Until the 2014–15 Ebola virus outbreak, Kenema was the only hospital in the world to have a special ward dedicated to treating hemorrhagic fever viruses. Staff at the clinic – from the nurses to the ambulance drivers – are all Lassa survivors, which gives them immunity to the disease. The TSRI scientists have a long-term collaboration with Kenema as part of a research program run by Tulane University that provided them with antibodies from survivors of Lassa fever. These antibodies could inactivate the virus, and they provided lifesaving protection to animal models. These were the kinds of antibodies researchers are hoping to elicit with a future Lassa virus vaccine.

In 2009, Hastie got to visit Kenema on a trip with Ollmann Saphire.

“I had been working on the project for two years with very little success at that point,” Hastie said. “Going to West Africa showed me how important it was to keep going.”

Like Ebola virus, Lassa fever starts with flu-like symptoms and can lead to debilitating vomiting, neurological problems and even hemorrhaging from the eyes, gums and nose. The disease is 50 to 70 percent fatal—and up to 90 percent fatal in pregnant women.

“Studying Lassa is critically important. Hundreds of thousands of people are infected with the virus every year, and it is the viral hemorrhagic fever that most frequently comes to the United States and Europe,” said Ollmann Saphire. “Kate’s study needed to be done.”

Tripod Shape Key to Future Vaccine Design

By creating mutant versions of important parts of the molecule, Hastie engineered a version of the Lassa virus surface glycoprotein that didn’t fall apart. She then used this model glycoprotein as a sort of magnet to find antibodies in patient samples that could bind with the glycoprotein to neutralize the virus.

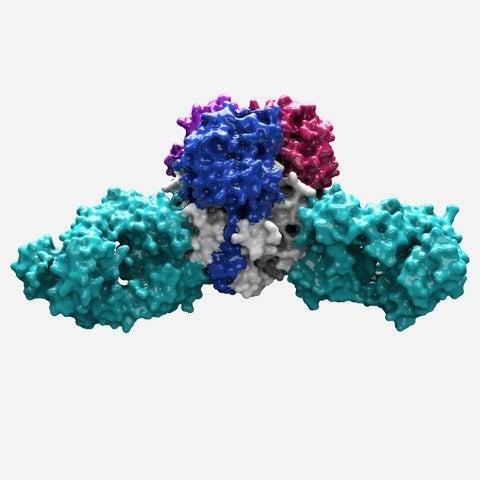

With this latest study she solved the structure of the Lassa virus glycoprotein, bound to a neutralizing antibody from a human survivor.

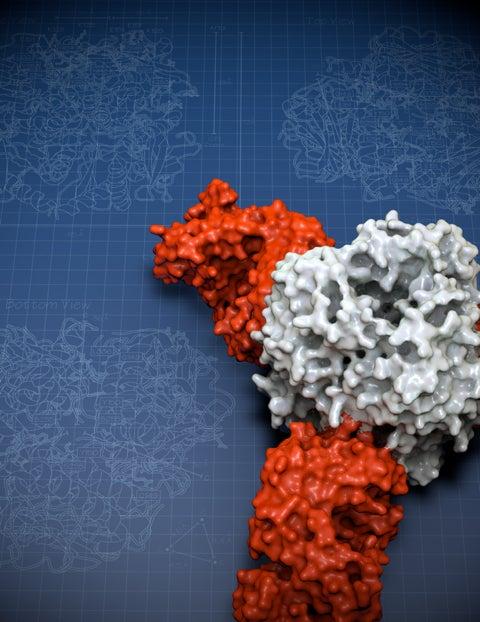

Her structure showed that the glycoprotein has two parts. She compared the shape to an ice cream cone and a scoop of ice cream. A subunit called GP2 forms the cone, and the GP1 subunit sits on top. They work together when they encounter a host cell. GP1 binds to a host cell receptor, and GP2 starts the fusion process to enter that cell.

The new structure also showed a long structure hanging off the side of GP1—like a drip of melting ice cream running down the cone. This “drip” holds the two subunits together in their pre-fusion state.

Zooming in even closer, Hastie discovered that three of the GP1-GP2 pairs come together like a tripod. This arrangement appears to be unique to Lassa virus. Other viruses, such as influenza and HIV, also have three-part proteins (called trimers) at this site, but their subunits come together to form a pole, not a tripod. The structure is also important because it can be used as a model to conquer related viruses throughout the Americas, Europe and Africa for which no equivalent structure yet exists.

“It was great to see exactly how Lassa was different from other viruses,” said Hastie. “It was a tremendous relief to finally have the structure.”

This tripod arrangement offers a path for vaccine design. The scientists found that 90 percent of the effective antibodies in Lassa patients targeted the spot where the three GP subunits came together. These antibodies locked the subunits together, preventing the virus from gearing up to enter a host cell.

A future vaccine would likely have the greatest chance of success if it could trigger the body to produce antibodies to target the same site.

Ollmann Saphire explained that Hastie accomplished something unique in structural biology. “The research started from scratch with the native, wild-type viruses in patients in a remote clinic—and went all the way to developing a basis for vaccine design. And the work was done almost entirely by one woman.”

Moving Forward with a Lassa Vaccine

The next step is to test a vaccine that will prompt the immune system to target Lassa’s glycoprotein.

As director of the Viral Hemorrhagic Fever Immunotherapeutic Consortium, Ollmann Saphire is already coordinating with her partners at Tulane and Kenema to bring a vaccine to patients.

The Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations, an international collaboration that includes the Wellcome Trust and the World Health Organization as partners, has recently named a vaccine for Lassa virus as one of its three top priorities. “The community is keenly interested in making a Lassa vaccine, and we think we have the best template to do that,” said Ollmann Saphire.

She added that with Hastie’s techniques for solving arenavirus structures, researchers can now get a closer look at other hemorrhagic fever viruses, which cause death, neurological diseases and even birth defects around the world.

Ollmann Saphire added that beamlines such as 12-2 at SSRL, which provided the X-ray beam used to finally determine the Lassa virus glycoprotein structure, along with its recent detector upgrades, are essential for ongoing advances in structural biology.

"This research highlights the power of crystallographic techniques that rely on advanced synchrotron facilities to combat the most challenging biological problems. The support of the DOE's Office of Science Biological and Environmental Research, the National Institutes of Health and private institutions such as TSRI enables us to make these resources available to the wider biomedical community," Cohen said.

In addition to Ollmann Saphire and Hastie, the following authors contributed: Michelle A. Zandonatti of TSRI; James E. Robinson and Robert F. Garry of Tulane University; Lara M. Kleinfelter and Kartik Chandran of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine; and Megan L. Heinrich, Megan M. Rowland and Luis M. Branco of Zalgen Labs.

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health and an Investigators in Pathogenesis of Infectious Diseases Award from the Burroughs Wellcome Fund. Research funding for the SSRL Structural Molecular Biology Program was provided by the DOE Office of Science and the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of General Medical Sciences.

This article is based on a press release by The Scripps Research Institute.

Citation: K. Hastie et al., Science, 2 June 2017 (10.1126/science.aam7260)

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

SLAC is a multi-program laboratory exploring frontier questions in photon science, astrophysics, particle physics and accelerator research. Located in Menlo Park, Calif., SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science.

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.